If someone says the word "strawberry" to you, what comes to mind?

Probably something sweet and red? Kind of round-ish, with some seeds and leaves? Maybe it reminds you of a farmer's market or a Beatles' song. Whatever pops in your head first, there's a lot of additional context swirling around up there than just the word itself.

Now imagine saying "strawberry" to a computer. How do we expect the computer, which lacks any of this knowledge or context, to understand what it is? Or that it's more similar to "apple" than "car"?

Welcome to the strange but fascinating world of vector embeddings, one of the key tricks that allows artificial intelligence (like ChatGPT) to understand and work with language. And while that may sound like it belongs in a computer science lab, it’s already part of your day-to-day life. The tools you use to summarize survey comments, scan council agendas, or organize documents might already rely on it.

So here’s a high-level guide to how meaning gets turned into math for city managers, finance directors, and anyone else whose job is increasingly brushing up against AI.

The big idea: meaning can be measured

Words can be ambiguous, slippery, and messy. But when you use enough of them, patterns start to emerge. Computers can learn those patterns and represent words as vectors (that is, as sets of numbers that describe where a word lives in a giant, multi-dimensional map of meaning).

If that's too abstract for you to handle right now, consider a hypothetical vocabulary that contains only four words: strawberry, blueberry, red, and blue.

If you wanted to encode the meaning behind these words, we might start by looking at two dimensions: fruity-ness and color.

In the fruity-ness dimension, strawberry and blueberry would be located near each other since they're both fruits while red and blue are not. In the color dimension, strawberry and red would be lined up (since they're red) while blueberry and blue would be closer together (since they're blue).

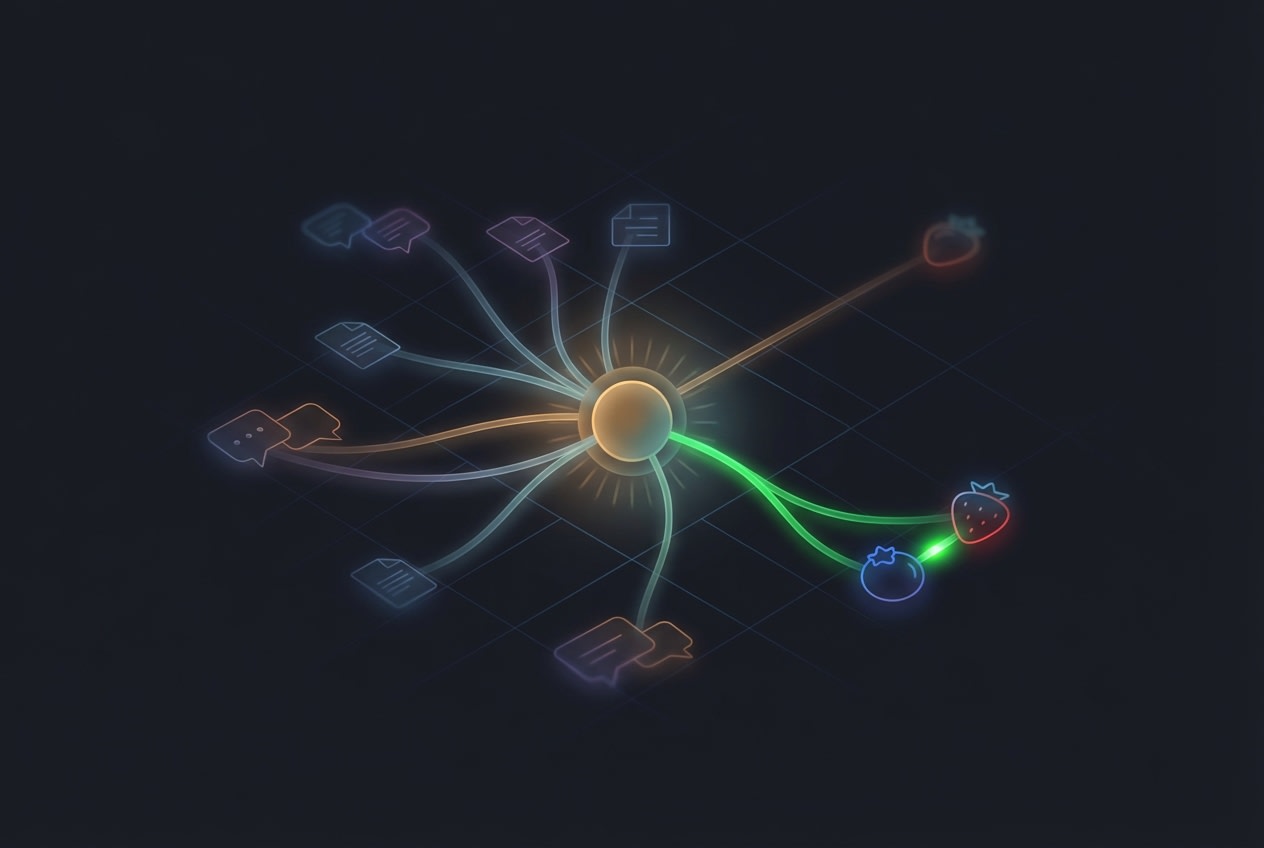

If were to graph this extremely simplified example, it might look like this:

Here you can see that the fruits are separated from the colors in the fruity-ness axis, which makes sense. You can also see that strawberry and red are at the same point in the color axis (since they're both red), while blueberry and blue are at the same point (since they're both blue).

If you imagine these locations as coordinates on a graph (strawberry = 1, 2; blue = 2, 1), you might remember from geometry class that we can calculate the distances between each point.

If you were to do this math, you'd also notice that red is closer to strawberry than blueberry. This "closeness" is what allows computer models to understand concepts that are more or less related to each other. That’s the key insight. It’s not about what the words look like. It’s about where they appear, how they’re used, and what they mean in context.

What's an embedding, actually?

An embedding is just a list of numbers. But each number corresponds to a dimension of meaning, like "fruity-ness" or "color," but multiplied out into hundreds of subtle, abstract features learned from billions of words.

In practice, that means the word "blueberry" might be represented by something like:

[0.62, 0.91, -0.03, 0.47, ..., 0.12]

…where each number helps define its location in a giant cloud of meaning.

Words that appear in similar contexts (say, "strawberry," "raspberry," or "fruit salad") end up with similar embeddings. They’re near each other on the map. Words that are used in totally different ways (like "dog" and "printer") end up far apart.

Why does this matter for cities?

At first glance, this may feel theoretical, but here’s why it’s useful: it allows AI tools to make connections between words, ideas, and documents in a way that reflects how humans use them, not just how they’re spelled.

That shows up in all kinds of local government scenarios:

- When summarizing public comments, an AI tool might group "too much traffic on Main Street" with "congested school drop-off zone" because both suggest circulation problems, even if they use different words.

- When analyzing budgets, it might understand that "public safety" includes fire, EMS, and police, even if each department uses its own terminology.

- When recommending zoning code changes, it can match phrases like "multi-family" and "medium-density housing" as related, rather than treating them as separate ideas.

In other words, embeddings help computers navigate the gray areas of human language; the parts where meaning is implied, not stated outright.

Embeddings aren't just for language!

While embeddings are often talked about in the context of language, the same approach can be used to represent just about anything: neighborhoods, 311 calls, permit applications, even crime incidents. Any time you have a dataset with multiple features (like time of day, location, type of offense, or dollar value) you can use embeddings to encode that data in a way that makes "closeness" meaningful.

For example, imagine mapping every building permit as a vector that captures its size, cost, zoning category, and construction type. Permits with similar profiles would cluster together, even if they came from different departments or used different form fields.

You could do the same for comparing crime reports, identifying areas with similar patterns across seemingly different neighborhoods. Or you could generate embeddings of census blocks based on demographics, income, and housing stock to identify parts of the city with similar profiles, which could be helpful for equity analysis, service planning, or prioritizing engagement.

The takeaway: embeddings are a way of measuring similarity across complex data, even when the connections aren’t immediately obvious.

What you don't need to know

You don’t need to know how to train an embedding model. You don’t need to write Python code or call an API.

But if you’re being pitched AI tools or exploring ways to make your city operations more efficient, it helps to know what’s happening under the hood. Especially when you’re being asked to trust those tools to summarize, extract, or even interpret human language on your behalf.

This isn’t magic, it’s math. And the math is surprisingly intuitive once you stop thinking about words as strings of letters, and start thinking about them as points on a map.